Nathaniel Hawthorne in Maine

Nathaniel Hawthorne in Maine

From an article by Herbert Edwards appearing in Downeast Magazine September, 1962

Nathaniel Hawthorne said later that the many years he spent at Raymond, on the shores of Lake Sebago, were the happiest of his life. He was twelve years old when his widowed mother left Salem, and with her son and two daughters, went to her brother’s lake-front house at Raymond. Here her brothers, Robert and Richard Manning, owned 12,000 acres of forest on the shores of the great lake that lay at the foot of the mountains.

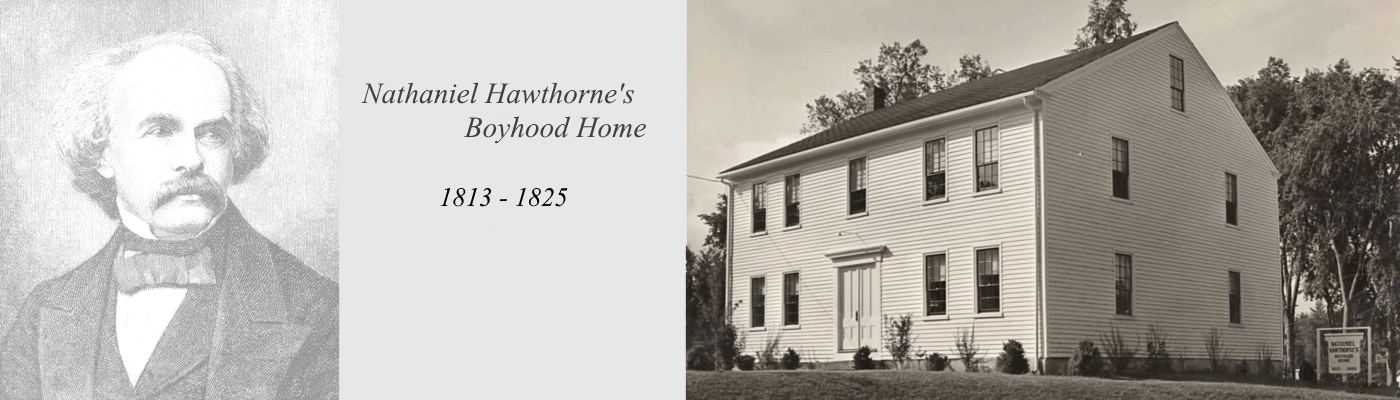

Beside the house, still standing, rushed Dingley Brook, which turned the big wooden wheel of Jacob Dingley’s grist mill before it poured into the lake.

Westward stretched an unbroken expanse of forest as far as the eye could see. Uncle Richard gave the young Nathaniel a shotgun from his large collection, and game of all kinds, from partridge to deer, was plentiful. The brook and lake were full of fish, and on many occasions the boy caught a dozen large trout in less than an hour. Sometimes he and his sister Elizabeth, who loved to walk, went far into the forest; often they would start off early in the morning and not return until late afternoon.

The mother and children, who had at first planned to stay only for the summer, prolonged their stay until autumn, and when winter came, they were still there. Nathaniel and Elizabeth skated over the chain of smaller lakes that stretched endlessly into the woods, and returned to read aloud to each other. Lying on the Turkey rug before the fireplace, they read the plays of Shakespeare, or the novels of Sir Walter Scott. Both were precocious children, for the boy had read Boswell’s Life of Johnson when he was four, long before he could understand it. It was probably Elizabeth’s learning that later condemned her to lifelong spinsterhood, scaring away the young men who were attracted by her loveliness. The healthy outdoor life in Maine benefited both youngsters, especially Nathaniel who, as a child in Salem, had not been strong, so that his school attendance was irregular. He suffered from some kind of crippling leg infection which the doctors were unable to cure, despite such unusual remedies as having him extend the leg from a lower-floor window of the house in Salem while a stream of water was poured on it from a top floor window. At Raymond this ailment completely disappeared, never to return, and as Elizabeth said, “He became a good shot an excellent fisherman, and grew tall and strong.”

Elizabeth also felt that Hawthorne the writer was born in Maine. She said that his imagination was stimulated by the beautiful scenery and by people – the woodsmen and small farmers who lived simple lives close to nature, different from the sophisticated townspeople of Salem. Many years were to pass before the great prose-poet of The Scarlet Letter emerged, but it is likely that he had his earliest inspiration at Raymond.

When Uncle Robert decided that his young nephew must prepare to enter college, Nathaniel disagreed vigorously. He was, he said, perfectly happy in the life he was leading, and he protested that “four years of my life is a great deal to throw away.” But the pressure Uncle Robert could exert on the entire family was too great; Nathaniel was forced to yield and return to Salem to be prepared for college. The college he chose to enter was Bowdoin, probably be cause it was close to Raymond, and easy of access, since Uncle Richard Manning owned the stage coach line that ran between Raymond and the coast.

On September 30, 1820, Uncle Robert took his nephew to Bowdoin. When they changed stages at Portland, Hawthorne met a young man from New Hampshire, Franklin Pierce, who was also entering Bowdoin. In personality the two boys were very different: Pierce, the future President of the United States, was a friendly, happy extrovert; Hawthorne was, despite his robust health, was shy, introverted and inclined to be moody and melancholy. But the two became close friends. Years later Hawthorne wrote the campaign biography of Pierce, and President Pierce appointed Hawthorne United States Consul at Liverpool, then the most lucrative post at the President’s disposal, a position from which Hawthorne retired after four years with $30,000 he had been able to save.

The entrance examinations at Bowdoin consisted mainly of going to the President’s office and demonstrating an ability to translate Latin and Greek. Hawthorne passed easily. Uncle Robert, who had been browsing about the campus meanwhile, was favorably impressed with what he saw, and that evening wrote to the boy’s mother: “Brunswick is a pleasant place, the inhabitants respectful and attentive to strangers, and the institution flourishing.”

Then a strange thing happened. Uncle Robert, before he left for home the next day, told Nathaniel that he had left some money for him at the college office. But when Hawthorne went to the office he was told that he was mistaken, that no money had been left there. Bowdoin was not an inexpensive college – room rent was eight dollars a term (higher than at Harvard) and the total expenses averaged $125 a year. The only inexpensive item was wood for the fireplaces in the students’ rooms, which cost one dollar a cord. Other items, such as whale them for one’s lamp, purchased from the grocery store in Brunswick and carried to the dormitory rooms in small copper cans, were much more expensive.

To meet his needs, Hawthorne borrowed money from a fellow student named Mason, whose parents were wealthy. After waiting a week for a remittance, he wrote home for money, but received no reply. A week later he wrote again, but there no response from Salem. At the end of October he had still received no reply to his letters. Even when November had passed, he was still borrowing from Mason. Eventually he received a bundle of clothes from home, but no money. His letters became desperate. Finally, on December 4 he got enough money from home to pay his debts. During his years at Bowdoin Hawthorne was to suffer the embarrassment of being completely without funds a number of times and to undergo the humiliation of having to borrow money from fellow students. Since his was an extremely sensitive nature, his mental suffering can easily be imagined. Moreover, his clothing was usually threadbare and inadequate, and this, of course, was another source of humiliation.

Whether Uncle Robert was really to blame or not we do not know. He may have underestimated the expense of a college education, or he may have been financially embarrassed at the time. Hawthorne’s mother, of course, had no resources to draw upon. She had had little money since Captain Nathaniel Hawthorne had died at sea when the children were small. And her son, it must be admitted, was always impractical and inept in managing his financial affairs. His relations with his publishers later is an example.

He always had only the vaguest idea of how much they owed him in royalties, and he never asked them for an accounting. Like Mark Twain in a later age in a later age, he made his publishers his bankers, and would send them bills to pay. He should have saved much more than $30,000 from the consulship at Liverpool, and he lost $10,000 of the $30,000 by lending it without security to one John O’Sullivan.

Hawthorne’s life at Bowdoin was strenuous. The bell summoning the students to prayers rang before sunrise. After prayers in the cold college chapel, they went breakfastless to their first class. There was no college dining hall in those days, and not until eight o’clock were they permitted to go to their boarding houses for breakfast. At nine, a two hour study period began, and then classes and study periods alternated throughout the day, with an hour out for dinner and an hour for supper, until nine, when everyone was expected to be in bed.

Like some other New England colleges at the time, Bowdoin still observed the Puritan Sabbath, which began at sundown on Saturday. Records reveal that Hawthorne and three other students were fined for “walking unnecessarily on the Sabbath day.” Visiting the tavern in town on Saturday night was a still more serious offense, and Hawthorne and his two friends received heavy fines for this.

His companions at Ward’s Tavern were Franklin Pierce and another friend, Horatio Bridge, from Augusta. It was Bridge who was responsible, some years later, for the publication of Hawthorne’s first volume of short stories, Twice Told Tales, by secretly guaranteeing the publisher against loss. Hawthorne said in the preface that Bridge was the first person to recognize his ability as a writer.

“I know not whence your faith came,” Hawthorne wrote, “but while we were Iads together at a country college – gathering blueberries in study hours under those tall academic pines, or watching great logs as they tumbled across the current of the Androscoggin, or shooting pigeons or gray squirrels in the woods; or bat-fowling in the summer twilight; or catching trout in the shadowy little stream which, I suppose, is still wandering riverward through the forest – two idle lads, in short (as we need not fear to acknowledge now) doing a hundred things that the Faculty never heard of, or else it had been the worse for us – still it was your prognostic of your friend’s destiny that he was to be a writer of fiction.”

Exactly what or how much Hawthorne wrote at Bowdoin is not definitely known. There, he may have begun Fanshawe, a novel about college life, for later his sister Elizabeth recalled a letter from her brother at Bowdoin in which he spoke of progress on a novel. Fanshawe was only a faint foreshadowing of the genius that was to come, but its beautiful style revealed the fledgling hand of a master. Today a copy of Fanshawe is a valuable rate book because after he had published it, anonymously, at his own expense, in 1828, three years after his graduation, he collected all the unsold copies and burned them – and only a small number had been sold. At Bowdoin he probably wrote the short stories which, when he had collected enough for a book, he called Seven Tales of My Native Land. These Hawthorne likewise burned when a publisher would not agree to print the volume promptly.

Hawthorne’s standing in his class was about in the middle – surprisingly good when we consider the amount of time he must have spent on creative writing, loafing, drinking at Ward’s Tavern, hunting, and walking. The afternoons until 4:30 were study periods, but he often managed to escape into the woods, where he hunted, or fished in the little river that flowed into the Androscoggin. Often be skipped his 4:30 class to walk to Maquoit Bay; his fines for absence from class in his junior year amounted to over ten dollars. Bridge and Pierce were willing companions on these escapades. Beneath Hawthorne’s surface taciturnity, on these walks Bridge found increasing evidence of the vivid imagination, the keen powers of observation, the hypersensitivity to the world about him that he felt certain were to make his friend a great literary artist.

The graduation exercises at Bowdoin in those days had many of the aspects of a country fair. Farmers and their families from miles around drove into Brunswick, hitched their horses to the railing of the college fence, and crowded about the tents where everything from gingerbread and pies to New England rum was sold. In the afternoon the crowd gathered around a platform near the pine grove to watch the graduation ceremonies and listen to the speakers. The class orator, young Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, read a brilliant paper on the need for a native American literature. The crowd applauded vigorously, little realizing that the speaker would himself become a great poet, or that the shy, handsome young man in the middle of the second row would become his country’s first great novelist.